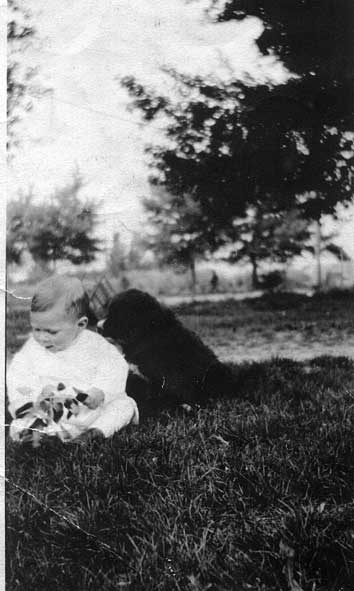

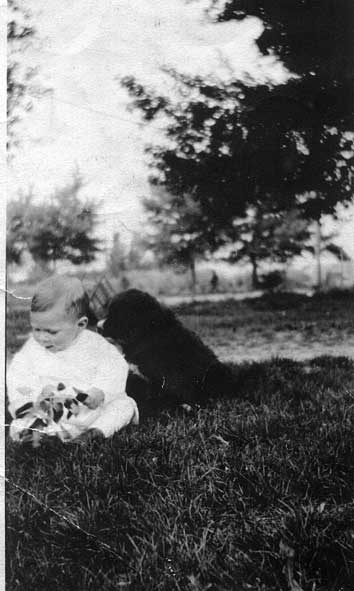

Forrest as a toddler, with family dog

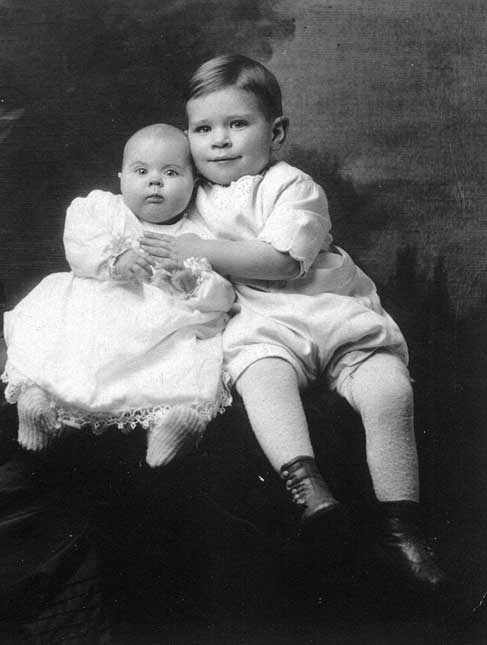

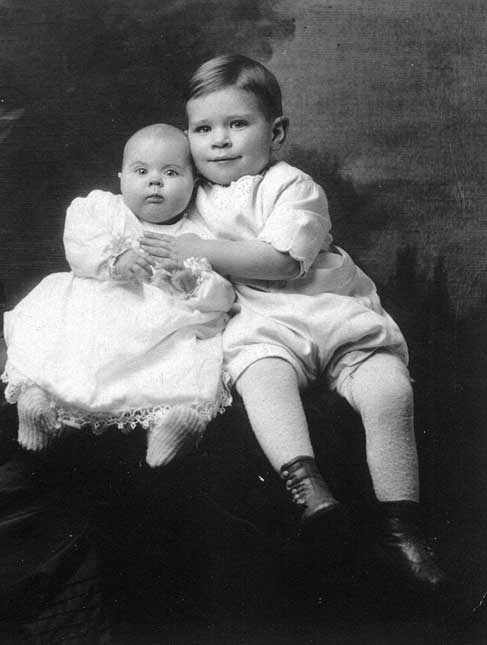

Forrest with sister Maxine, probably early 1920

Forrest as a toddler, with family dog |  Forrest with sister Maxine, probably early 1920 |

Early in life, Forrest was closely acquainted with the hard, industrious life of a farmer. He was born on March 7, 1918, the first child of Archie Earl and Florene Davis Buchanan. They lived on a 40 acre farm in Venice, Utah. Forrest took care of the sheep from a young age. Being the oldest, many tasks fell to him in helping his father. Early on, he also showed a resourcefulness that would be a hallmark of his life. Regardless of the situation, he would craft a solution. As a boy, in his summer duties, he was responsible for herding about 30 to 40 head of sheep. He needed the help of dogs to keep the animals in control. One bird dog was not nearly as interested in the sheep as in a game of fetching sticks, so Forrest would throw the stick into the area of the sheep that needed to move, and the dog would dive into the flock after the stick, which frightened the sheep into moving. Another more serviceable dog was also used in the work, but unfortunately had acquired a taste for sheep flesh and would nip at the poor creatures. To solve this problem, Forrest fashioned a make-shift muzzle out of a tin can, cutting out both ends and strapping it over the maul of the dog. The dog could bark and drive the sheep without injuring them and could still run to the stream for a drink through the open end of the can.

Forrest also used his inventiveness in entertaining others, especially his family. He built a cart and trained the dog to pull it wearing a harness he made. He explains, " I had a lot of enjoyment with this dog. One time I was giving my sister a ride in the cart. We got near some cows and he took after them. He really gave my sister a ride. The cart went over a bump, and threw her out, and before I got the dog stopped, the cart was a wreck. The axle broke on the cart and she was dumped out in some weeds. It didn't hurt her, just a good scare."

In their farm experiences, they worked a lot with animals. Forrest tells a story of a horse that had more sense than the people did. "We had a real special riding horse. You could put a small child on his back, and the horse would walk real slow, then put a six or eight year old on and they could make him walk fast, then put a teenager on and they could make him trot. Only an adult could make him go fast. One time my father was going down to the farm (everyone lived in town and had their farms surrounding the town) and he stopped to talk to one of my uncles. He was still on the horse. He had been there for a little while. When he went to leave, the horse wouldn't move. My dad got really out of sorts with the horse. Just then another neighbor came running towards them yelling not to move that horse, because standing between the horse's front legs was a little boy with an arm around each leg. So the horse was real special. As soon as they got the boy away from the horse he moved, so Dad was really sorry of mistreating the horse."

In their work with sheep, he relates: "My father always had a lot of sheep while in Venice, and every Spring they would have to be sheared. My father had his own shearing outfit and he would shear them and I would tie fleeces and tromp them in those huge wool sacks. They were three feet in diameter and about ten feet long. There was a scaffold that the sacks could be hung on. We had a metal ring, just the diameter of the sacks, then by folding the top over the ring, and fasten it with a few nails, then the wool could be tossed in, then I would climb in and tromp it tight and hard. We would poke small quantities of wool in the corners at the bottom, then tie the corners to form handles to maneuver them around when loading them on the trucks or wagons. My father would take his shearing outfit to all the farmers around town, who had sheep and shear all their sheep. So I had lots of experience of tromping wool."

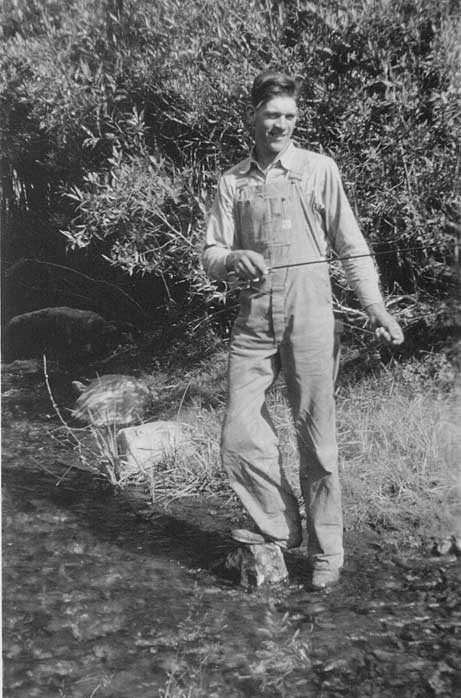

Another aspect of Forrest's life that carried into my life was his love of the outdoors, camping and exploring. He explains about his home town, "The town of Venice has the Sevier River winding through the center of the town. I used to have a lot of fun around this river. We could swim, fish and wade. Sometimes we would be only clad in a shirt and with a pitchfork we would go up the river and spear fish, mostly carp, and throw them out on the bank. It brings back fond memories."

He later tells of an experience he had with his father: "In the late spring the wild flowers would cover whole hillsides in the most beautiful array of colors, really a sight to behold. On one occasion in the mountains, after we had checked on the cattle, we decided to go fishing. It was late afternoon. We were having such good luck that it started to get dark on us before we started for camp. Somehow we took the wrong fork of the stream and wound up in an area we weren't acquainted with, and we became lost. We spent several hours trying to find our way out, but to no avail. So Dad started to holler as loud as he could. He soon got hoarse, but someone heard us and started to holler back. We finally got to their camp about eleven o' clock at night, and found that we were about five miles from our camp. It was quite an experience to remember."

He later tells of an experience he had with his father: "In the late spring the wild flowers would cover whole hillsides in the most beautiful array of colors, really a sight to behold. On one occasion in the mountains, after we had checked on the cattle, we decided to go fishing. It was late afternoon. We were having such good luck that it started to get dark on us before we started for camp. Somehow we took the wrong fork of the stream and wound up in an area we weren't acquainted with, and we became lost. We spent several hours trying to find our way out, but to no avail. So Dad started to holler as loud as he could. He soon got hoarse, but someone heard us and started to holler back. We finally got to their camp about eleven o' clock at night, and found that we were about five miles from our camp. It was quite an experience to remember."

Also on the farm, he learned the value of natural resources. Water especially was a precious commodity. "We had a 40 acre farm in Venice, and were able to raise hay and grain and sugar beets, but there was a real water shortage. We had to utilize every drop, sometimes there would only be one watering for all the summer's hay crop. Every type of crop had to be furrowed off so the benefit of the irrigation could be reached as far as possible."

When it came to harvesting their crops and getting ready for winter, they again used their innate resourcefulness. "In harvesting our alfalfa hay, after it was cut, we would pile it with a dump rake. Then after it was cured and dry we would haul it loose on a hay rack. All we had for wagons were the old iron tire wagons. We had a unique way of stacking our hay. We had what we called a Vee rope. This rope was about an inch and a half in diameter and it was long enough to cross the wagon twice. It would be placed on the wagon in the shape of a vee, with a loop on the vee side and on the ends a knot. Then the hay would be stacked on the rope and tromped. When we got a good size load on we would haul it to the stack, and there on the stack we would have two heavy ropes as long as we wanted to make the stack. Each rope had a loop on the end, so they could be attached to the knots on the Vee rope under the load of hay. Then we had a steel cable that was twice as long as the stack. The cable has a hook on it. We throw the cable over the load of hay and hook it in the loop on the Vee rope. Then I would take the team of horses off the wagon and take them around behind the stack and hook on the cable. Dad would take the pitch fork and stick it in the hay and wrap the other ends of the long ropes around the pitch fork handle to anchor the ropes. So while Dad was holding the ropes, I with the team would roll the load of hay right up the stack wherever he wanted it. Then he would release the ropes and I would pull them free. Then after the hay was leveled out I would have the ropes and cable ready to be placed on the stack for the next load, then hitch the team up and repeat the process. We could build stacks thirty to forty feet high and sixty to seventy feet long. In the winter time, when we feed the hay we had a hay knife that we could cut a section off the end, then as that was used down to the ground, then we could start a new cut and so on. We cut all our grain with a binder with it cut this way it would be in bundles. Then when the grain was dry we would haul it and stack it in round stacks about twenty feet high. Then the threshing machine would come and they would pitch the bundles in the machine. After the grain was separated, the straw was blown out into a stack. As kids we sure had a lot of fun on these straw stacks."

In his later life, Forrest wrote a thoughtful note of thanks to his father, then serving a mission in Florida. This letter was written around 1964. Here is an excerpt describing his life with his father as a youth: "My mind wanders back to some of the things that have transpired while growing up. I think of the times I helped Dad drive cattle and sheep up on the range. And how we would visit the sheep camps and have our meals, such as sour dough bread and all that goes with it. I remember one late spring when we got up by cold springs that the wild flowers were all out in bloom. It was a most magnificent sight to see. There were all colors imagineable.

We would see some of the wild game to excite our pleasure.

The fishing trip up in U M when we got lost and Dad began to holler, and after lots of walking and yelling someone soon answered us and we got back safely. I think of the times working with the sheep, Dad teaching me how to shear a sheep, of tromping wool, and herding sheep. Learning how to do things on the farm, that has been a great help to me ever since."

Forrest was raised in religious family, his grandparents and great-grandparents having embraced the gospel of Jesus Christ and joining the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in early days of the church. The area they lived in was settled by both his father's and mother's famlies in pioneer times. Forrest was blessed in the church one month to the day of his birth, by J. C. Cowley in the Venice Ward. He was baptised in the Stake Tabernacle in Richfield on 6 June 1926 by Wayne Christian, confirmed by A. W. Buchanan the following day. He was involved in church activity, as shown by church records of his priesthood ordination of Deacon on 6 July 1930. He received a certificate on 14 April 1933 for completing 3 years of Junior Seminary.

Life in Northern Utah

Forrest was a member of the FFA (Future Farmers of America), and along with his activities, he participated in an activity in faraway Logan. He relates: "While we were living in Venice, they had what was called the Farmers Encampment, which was held on campus of the Utah State Agricultural College at Logan. There were farmers from throughout the State that gathered there, driving their old cars. It was a real experience. They furnished all the buttermilk you could drink. There were lots of activities and games of all kinds and gatherings for the parents. One thing that I vividly remember was that the old Model T Fords had gravity feed gas and on some of those steep dugways, they would have to be turned around and backed up the hill to get to our destination."

Forrest was a member of the FFA (Future Farmers of America), and along with his activities, he participated in an activity in faraway Logan. He relates: "While we were living in Venice, they had what was called the Farmers Encampment, which was held on campus of the Utah State Agricultural College at Logan. There were farmers from throughout the State that gathered there, driving their old cars. It was a real experience. They furnished all the buttermilk you could drink. There were lots of activities and games of all kinds and gatherings for the parents. One thing that I vividly remember was that the old Model T Fords had gravity feed gas and on some of those steep dugways, they would have to be turned around and backed up the hill to get to our destination."

This was before 19 May, 1935 when he was ordained a Priest in the Logan 5th Ward, and after his sophomore year of high school in Richfield, because he then states, "It wasn't long after this that Dad wanted to try out for a Forest Ranger, so after my Sophomore year we moved to Logan, Utah, and Dad went to College to train for the Forest Service. He went for two years then found there were no openings. So we moved out to North Logan and rented a farm. We lived there about a year and a half. In the meantime Dad spent a lot of time searching up through Idaho and Northern Utah for a piece of ground to buy. He finally located an eighty acre farm in West Tremonton and bought it for 8,000 dollars. It had a big home on it, also a barn, granary and other small buildings. Dad got a loan from the Federal Land Bank."

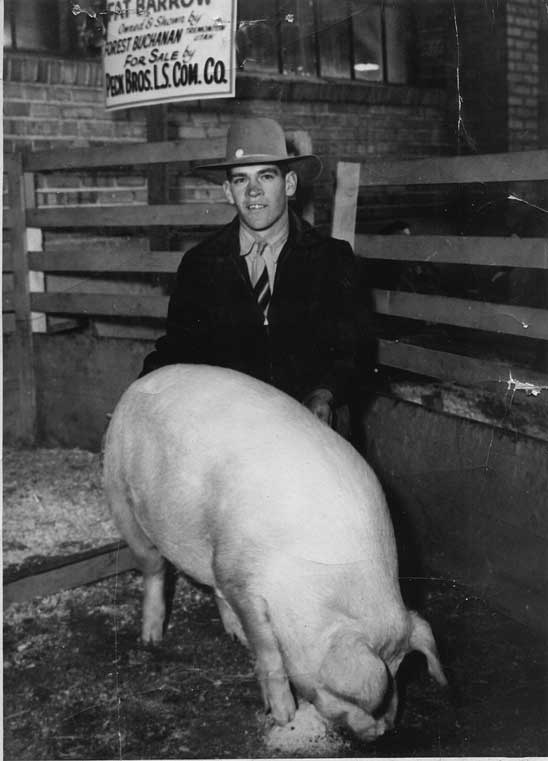

During this time Forrest was expected to help with the support of the family and had to quit school before graduating from high school. He did a lot of work on the farm, something he had a lot of experience with and a skill that he relied upon for much of his life to support himself and his family. During these times, there was an interesting experience he had with raising pigs. "...one spring we had a litter of pigs. They were pure white, they had made a remarkable gain in weight. They were six months old and they averaged two hundred and fifty pounds each. Well, the Ag teacher was out to our farm one day and he saw those pigs, and said that we just had to get them in the stock show. (The Ogden Livestock Show was just starting.) So we took him up on it and entered them in the livestock show. I took first place in the Junior division and the open in both the single pig and the pen of three, and Champion of the Junior Division and Grand Champion of the whole show in the swine department. This happened in 1938. There were six pigs in the litter." The article in the paper reports: "Dominant figure among the fat swine showmen Saturday was six-foot, two-and-one-half-inch Forrest Bunchanan (sic), 19, who showed his Chester Whites to the grand championship class in both Future Farmer and open classes to continue the record of Tremonton-Garland Future Farmers. ... But Buchanan is a Tremonton-Garland F.F.A. alumnus only by adoption. He went to school his first F.F.A. year at Richfield. And, so did his father, A. E. Buchanan. ... Jerry W. Buchanan, 4-year-old brother and son of the unique family of stockmen, is next in line for honors. But even now he is the assistant to his father and big brother and a most severe "critic" of the training and feeding routine they use in fitting their animals for the ring."

Forrest tells once when his father got quite frustrated with him. He asked Forrest to go get the car keys, but all he could hear was "corkies". They both laughed a lot when they finally worked out the confusion together. I am not sure when this happened, but it could have been around this time. Archie called Forrest, "Bud" and relied on him a lot to help around the farm. Forrest also worked on other farms in the area over the next few years.

Military Service

I do not have much information about Forrest's young adult life. He was ordained an Elder in Tremonton on Feb. 16, 1941. Less than a month later, he entered military service in the United States Army Field Artillery with a group of over 90 men from the Garland area (Bear River Valley) on March 12, 1941, and was stationed beginning in San Luis Obispo, California. His group was stationed in that area until the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. He had his first training there for about 13 weeks. From the pictures in his photo album, it looks like he travelled on maneuvers to Chehalis, Washington from August 6th to the 30th. He was in a number of other places, mainly in California and Washington including a trip to the Los Angeles area around November 11th and San Francisco around Christmas of that year. His group was moved to Escondido, California the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Some of his group was later transferred to Fort Lewis Washington. A postcard written to his parents dated October of 1942 seems to indicate that he was then travelling to Fort Lewis, with an address there, but he may have been in Washington a while before that time. A newspaper article states that they were sent to do desert training in the Yakima Desert. Most of his outfit were sent to Maui, Hawaii in preparation for service in the Pacific region of the war.

Forrest served in the field artillery in the Army |

An apt description of army soldiers |

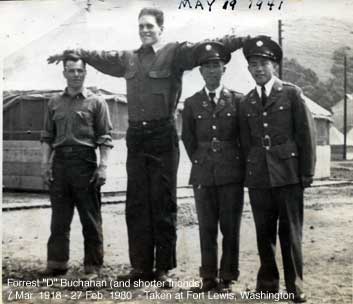

There are some good pictures of Forrest in his army activities. As is evident in some pictures, it he enjoyed comparing his large stature with the size of his fellow soldiers. One particularly humorous photograph shows Forrest standing up with his arms extended and three friends all standing under the level of his arms, emphasizing the size difference. The people in the picture are (left to right): Blaine Thompson, Forrest, Jimmy Kuwata and Sam Sato. This is typical of his humor. I find it interesting, too, that two of these friends are of Japanese ancestry, notable because the photograph was taken a few months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, after which our nation became quite paranoid about Japanese people, putting many in interment camps for the duration of the war. According to the newspaper article, though, "five Japanese-American boys in our group were taken and sent to fight in Europe where their unit became highly decorated". This transfer is implied to have taken place almost immediately after the attack in Hawaii.

There are some good pictures of Forrest in his army activities. As is evident in some pictures, it he enjoyed comparing his large stature with the size of his fellow soldiers. One particularly humorous photograph shows Forrest standing up with his arms extended and three friends all standing under the level of his arms, emphasizing the size difference. The people in the picture are (left to right): Blaine Thompson, Forrest, Jimmy Kuwata and Sam Sato. This is typical of his humor. I find it interesting, too, that two of these friends are of Japanese ancestry, notable because the photograph was taken a few months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, after which our nation became quite paranoid about Japanese people, putting many in interment camps for the duration of the war. According to the newspaper article, though, "five Japanese-American boys in our group were taken and sent to fight in Europe where their unit became highly decorated". This transfer is implied to have taken place almost immediately after the attack in Hawaii.He was discharged from the service because of some problems with his feet. I understand that this happened a short time prior to his unit being shipped away. He often told us that it was during his stint in the Army that he lost his beautiful wavy hair, blamed on army hats and/or the medical treatments he received in the Army.

Tremonton and Idaho Falls

According to letter envelopes and tithing receipts found among his papers, It appears that Forrest lived in Tremonton in 1943 through 1945. The letters were dated 1943 and were from Myrtice Mundy of Augusta, Georgia. She was quite an artist by the look of her drawings on the envelopes. I remember Dad saying that she was quite interested in him, but he did not share the affection.

Sometime around November or December of 1945 Forrest moved to Idaho Falls, Idaho. According to his written history: "In 1945 I left home and went to work up in Idaho. I worked on a dry farm in Cleveland. Then later on I worked in the potatoes in Blackfoot, then in a grocery store in Idaho Falls. While there I did a lot of Temple work. A dear friend named Walter Clark, who was a temple worker and had a farm in Squirrel, Idaho offered to send me on my mission which I accepted. "

In February, 1947 he received his mission call to the New England States Mission in a letter dated Feb. 6, 1947 from Pres. George Albert Smith. At the time, missionaries were ordained to the office of Seventy. He was ordained on Mar. 10, 1947 by Oscar A. Kirkham. His mission certificate is dated Mar. 12, 1947.

Appendix A - Life Timeline

Appendix B - Histories and journals

Appendix C - Mission Journal

Appendix D - Recipes